Machine Learning Trading

Q-Learning

11 minute read

Notice a tyop typo? Please submit an issue or open a PR.

Q-Learning

Overview

Recall that Q-learning is a model-free approach, which means that it does not know about, nor use models of, the transition function, , or reward function, . Instead, Q-learning builds a table of utility values as the agent interacts with the world, which the agent can query at each step to select the best action based on its current experience. Q-learning is guaranteed to provide an optimal policy.

What is Q

We know at a high level what Q-learning is, but what is Q? Q can either be written as a function, , or a table, . In this class, we think of Q as a table. Regardless of the implementation, Q provides a measure of the value of taking an action, , in a state, .

The value that Q returns is actually the sum of two rewards: the immediate reward of taking in plus the discounted reward, the reward received for future actions. As a result, Q is not greedy; that is, it does not only consider the reward of acting now but also considers the value of actions down the road.

Remember that what we do in any particular state depends on the policy, . Formally, is a function that receives a state, , as input and produces an action, , as output.

We can leverage a Q-table to determine . For a particular state, , we can consult the Q-table and, across all possible actions, , return the particular action, , such that is as large possible. Formally,

Note the syntax of . The solution to the equation is the value of that maximizes .

If we run Q-learning for long enough, we find that eventually converges to the optimal policy, which we denote as . Similarly, the optimal Q-table is .

Clearly, the Q-table is essentially for developing the policy, and we have assumed here that we have the Q-table at our disposal. We need to consider next how we might build this table from the experience our agent gains by interacting with the environment.

Learning Procedure

Let's now focus on how we train a Q-learner.

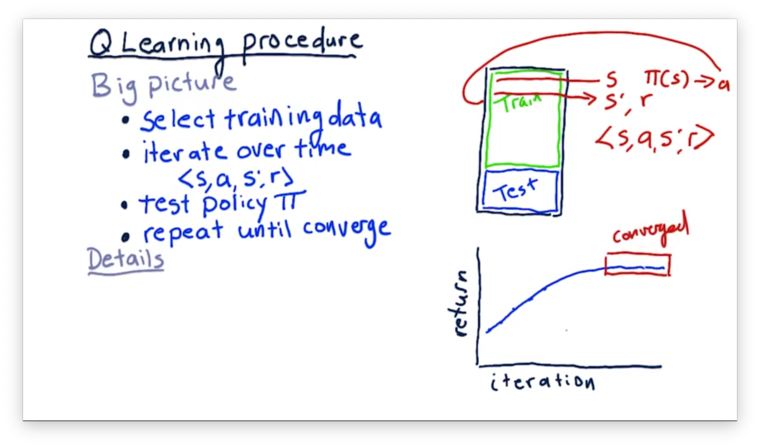

Recall how we partition our data for a machine learning problem: we need a larger training set and a somewhat smaller testing set. Since we are looking at stock features over time - our data set is a time series - we have to ensure that the dates in the training set precede those in the test set.

We then iterate through each time step in our training set. We evaluate a row of data to get our state, . We then consult our policy, , for that to get an action, . We execute that action and observe the resulting state, , and our reward, .

For each training example, we produce an experience tuple, containing , , , and . We use this tuple to update our Q-table, which effectively updates our policy.

Updating our Q-table requires us to have some semblance of a Q-table in place when we begin training. Usually, we initialize a Q-table with small random numbers, although various other initialization setups exist.

After we have finished iterating through our training data, we take the policy that we learned and apply it to the testing data. We mark down the performance and then repeat the entire process until the policy converges.

What do we mean by converged? Each time we train and then test our learner, we get some measure of performance. We expect that performance is going to improve with each training session steadily; however, after a point, we reach the best possible policy for our data, and performance ceases to improve with successive trainings. At this point, we say that our policy and the optimal policy have converged.

Update Rule

After reading in some state, , from the environment, a robot must select an action, , to take. To do so, it queries the Q-table to find the action that corresponds to the maximum Q-value for that state. Taking an action produces two values: a new state, , and a reward, . The robot uses the experience tuple, , to update its Q-table.

There are two components to the update rule. The first part concerns the current Q-value for the seen state and taken action: . The second part concerns an improved estimate, , of the Q-value. To combine the two, we introduce a new variable: .

We refer to as the learning rate. It can take on any value between 0 and 1; typically, we use 0.2. Smaller values of place more weight on the current Q-value, whereas larger values of put more emphasis on . We can think about this in another way: larger values of make our robot learn more quickly than smaller values.

When we talk about the improved estimate, , for the Q-value, we are talking about the sum of the current reward, , and the future rewards, . Remember that we have to discount future rewards, which we do with .

Similar to , usually ranges from 0 to 1. A low value of corresponds to a high discount rate and means that we value later rewards less. A high value of indicates the opposite. Indeed, using a value of 1 means that we value a reward 20 steps into the future as much as a reward right now.

If we think about the future rewards, , what we are looking for is the Q-value for the new state, . That is, the future reward for taking action in state is that action, , that maximizes the Q-value with regard to state .

Two Finer Points

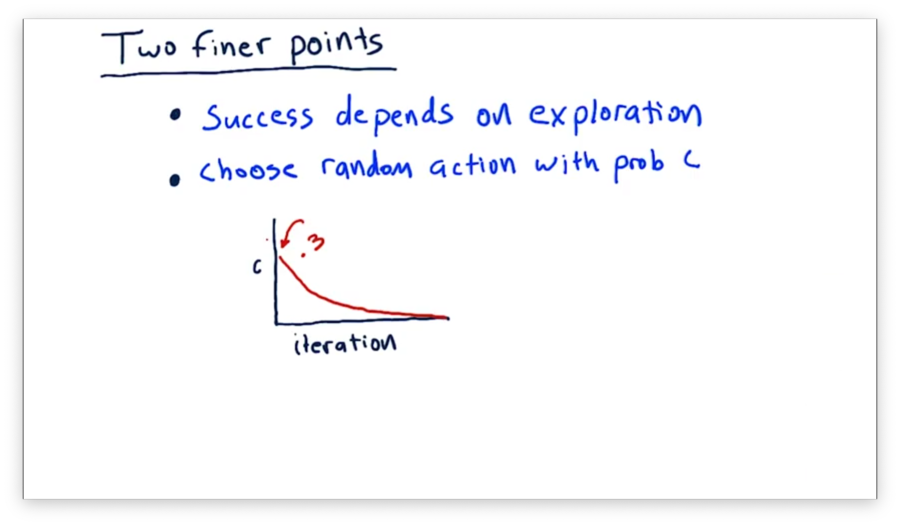

The success of Q-learning depends to a large extent on exploration. Exploration helps us learn about the possible states we can encounter as well as the potential actions we can take. We can use randomness to introduce exploration into our learning.

Instead of always selecting the action with the highest Q-value for a given state, we can, with some probability, decide to choose a random action. In this way, we can explore actions that our policy does not advise us to take to see if, potentially, they result in a higher reward.

A typical way to implement random exploration is to set the probability of choosing a random action to about 0.3 initially; then, over each iteration, we decay that probability steadily until we effectively don't choose random actions at all.

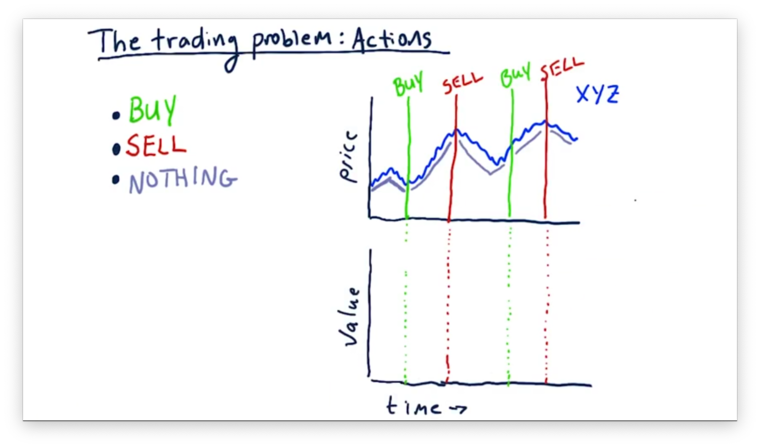

The Trading Problem: Actions

Now that we have a basic understanding of Q-learning, let's see how we can turn the stock trading problem into a problem that Q-learning can solve. To do that, we need to define our actions, states, and rewards.

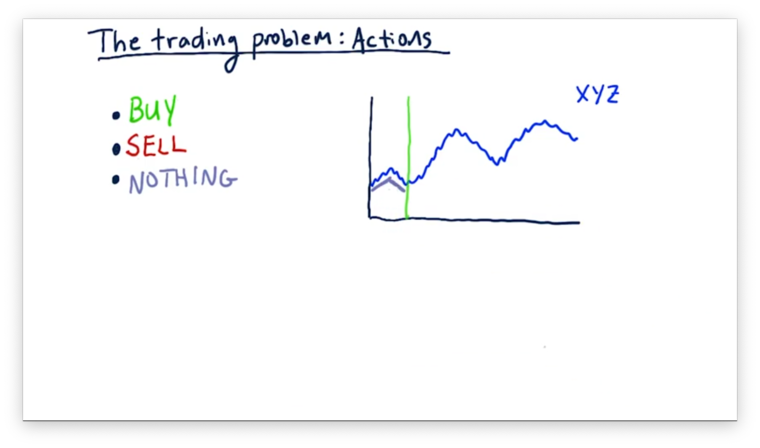

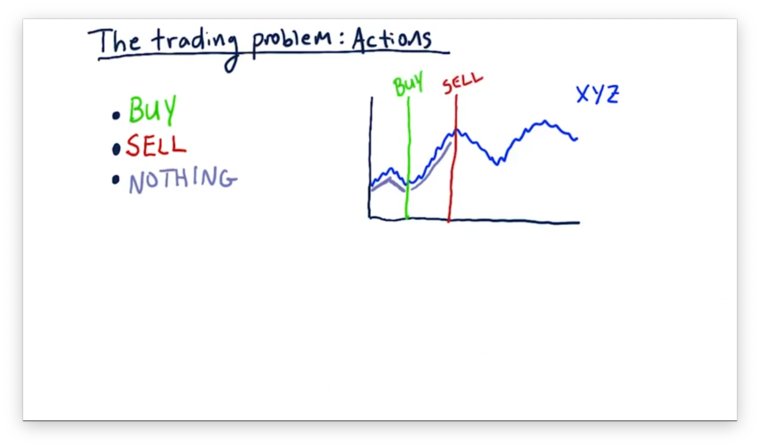

The model that we build is going to advise us to take one of three actions: buy, sell, or do nothing. Presumably, it is going to tell us to do nothing most of the time, with a few buys and sells scattered here and there.

Let's look at stock XYZ.

The state that our model reads in here are various factors - such as technical indicators - concerning this stock. Our model continuously reads in state, advising us to do nothing until something triggers and we see a buy action.

After we execute the buy action, our model tells us to do nothing until we enter a state in which it advises us to sell.

We can continue this process through the rest of our time series.

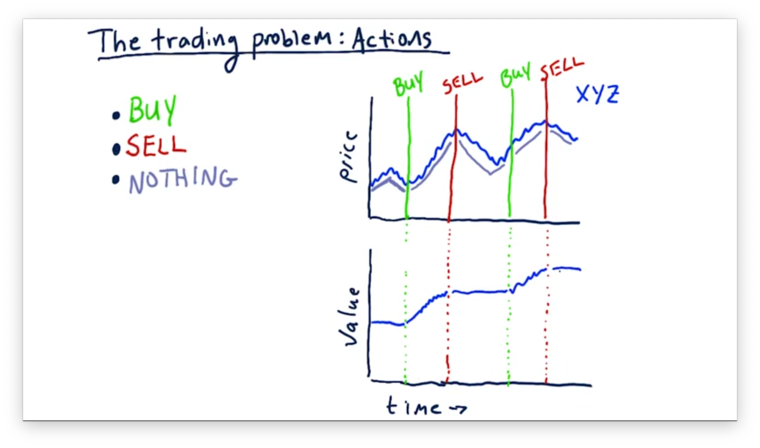

Let's consider now how these buys and sells affect our portfolio value. Our portfolio value before our first buy corresponds to whatever money we have in the bank. Once we execute a buy action, our portfolio value rises with the price of the stock. Once we sell, our portfolio hovers at the price of the sale. We can see how the value of our portfolio relates to the actions we take below.

The Trading Problem: Rewards Quiz

The rewards that our learner reaps should relate in some way to the returns of our strategy. There are at least two different ways that we can think about rewards.

On the one hand, we can think about the reward for a position as the daily return of a stock held in our portfolio. On the other hand, we can think about the reward for a position being zero until we exit the position, at which point the reward is the cumulative return of that position.

Which of these approaches results in a faster convergence to the optimal policy?

The Trading Problem: Rewards Quiz Solution

If we choose the delayed paradigm - where the reward is zero until the end of the trade cycle - the learner has to infer the correct sequence of actions leading up to the final action that brought about the large windfall. If we reward a little bit each day, however, the learner can learn much more quickly because it receives much more frequent rewards.

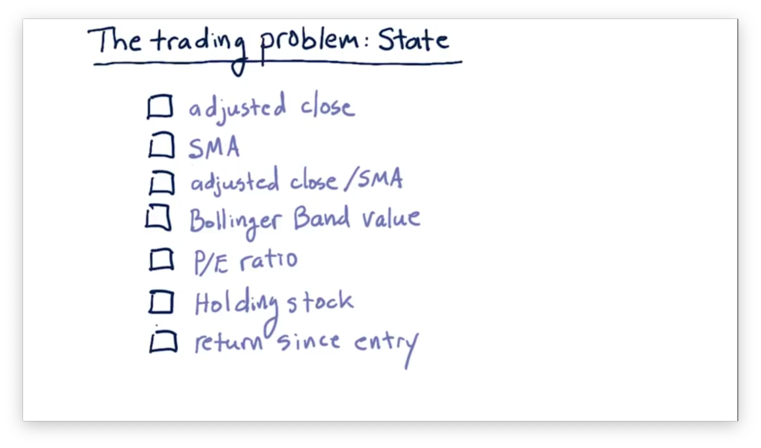

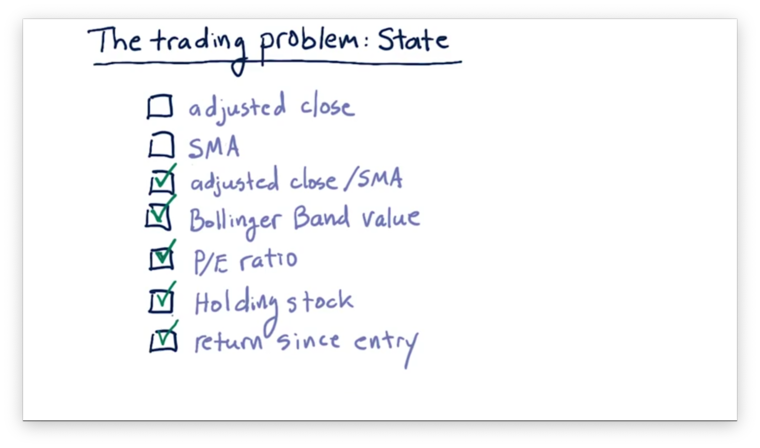

The Trading Problem: State Quiz

Consider the following factors and select which should be part of the state that we examine when selecting an appropriate action.

The Trading Problem: State Quiz Solution

Neither adjusted close nor SMA alone are useful components of the state because they don't particularly mean much as absolute values. For example, if GOOG closes at $1000 per share, and XYZ closes at $5 per share, we cannot determine, based on that information alone, whether we should buy, sell, or hold either of those stocks.

However, the ratio of adjusted close to SMA can be a valuable piece of state. For example, a positive ratio indicates that the close is larger than the SMA, which may be a sell signal. Additionally, other technical and fundamental indicators such as Bollinger Bands and P/E ratio can be essential parts of our state.

Whether or not we are currently holding a stock that we are examining is an important piece of state. For example, if we are holding a stock, it might be advantageous to get rid of it. Alternatively, if we are not holding a stock, we may not want to sell because we don't want to enter a short position.

Finally, our return since we entered a position might be a piece of our state. For example, we might decide to sell off a particularly volatile stock after we have locked in some amount of return.

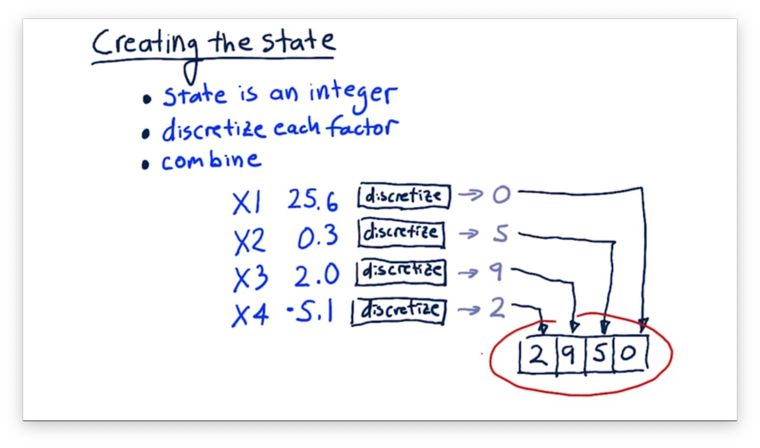

Creating the State

In Q-learning, we need to be able to represent our state as an integer; that way, we can use it to index into our Q-table, which is of finite dimension. Converting our state to an integer requires two steps.

First, we must discretize each factor, which essentially involves mapping a continuous value to an integer. Second, we must combine all of our discretized factors into a single integer that represents the overall state. We assume we are using a discrete state space, which means that our overall state represents at once all of the factors.

For example, we might have a state containing four different factors, each of which is a number. We pass each of these factors through its discretization function to map its value onto an integer from 0 to 9. Finally, we "stack" the discretized factors, digit by digit, to form the final state.

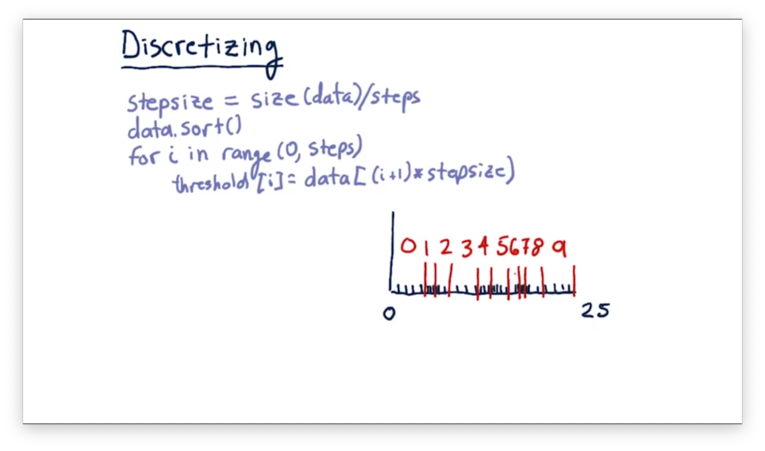

Discretizing

Discretization is a process by which we convert a real number into an integer across a limited scale. For example, for a particular factor, we might observe hundreds of different real values from 0 to 25. Discretization allows us to map those values onto a standardized scale of integers from, say, 0 to 9.

Let's look at how we might discretize a set of data. The first thing we need to do is determine how many buckets we need. For example, if we want to map all values onto a number between 0 and 9, we need 10 buckets.

Next, we determine the size of our buckets, which is simply the total number of data elements divided by the number of buckets. For example, with 10 buckets and 100 data elements, our bucket size is 10.

Finally, we sort the data and determine the threshold for each bucket based on the step size. For example, with 10 buckets and 100 sorted data elements, our threshold for the discretized value, 1, is the tenth element, our threshold for the discretized value, 2, is the twentieth element, and so on.

A consequence of this approach is that when the data are sparse, the thresholds are set far apart. When the data is very dense, the thresholds end up being very close together.

To discretize an incoming feature value, we simply find which threshold that value passes. For example, a value greater than the fortieth sorted element but less than the fiftieth would have a discretized value of 4.

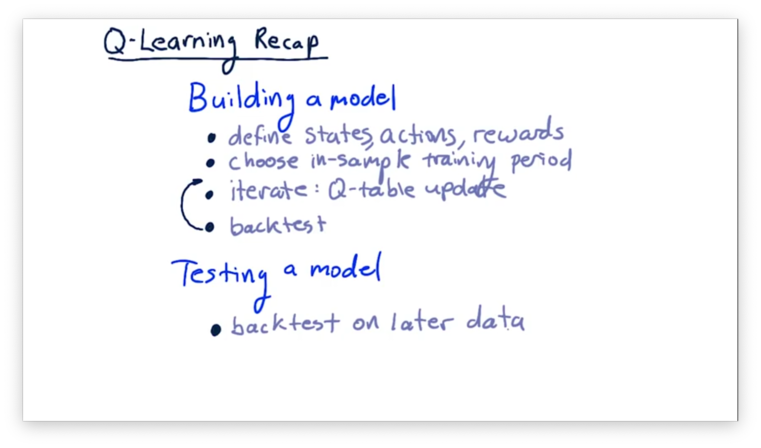

Q-Learning Recap

OMSCS Notes is made with in NYC by Matt Schlenker.

Copyright © 2019-2023. All rights reserved.

privacy policy